Chronic kidney disease (CKD) - Stages 3b – 5

Complications and treatment for late stage CKD

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a lifelong condition. The kidneys gradually stop working as well as they should. This usually happens over many years.

In stages 3b to 5 CKD – the later stages of CKD – many children start to have symptoms as their kidney function is reduced. These symptoms are different for each child with CKD. Water and salts can build up in the body, which may lead to swelling and high blood pressure. Some children get more tired than usual, feel sick (nausea) or are sick (vomit), cannot or do not want to eat as much, and may not grow as well.

Your child’s healthcare team will make sure your child gets the right tests and treatments at each stage of the disease, and regular assessments to check that he or she is growing well.

Your child may need to take some medicines to treat the symptoms – changing the types or doses of medicines as needed. He or she may need to eat a different diet and drink fewer or more fluids (such as water and juice), and may need to use a feeding tube. You will have lots of support to make sure your child gets the right nutrition. Your child’s healthcare team will talk to you about any other treatments that may benefit your child.

CKD is a complicated disease. You and your child will learn more over time about how to help manage the condition and what to expect. While it is not possible to recover from CKD, specialist care will help your child live as full and healthy a life as possible.

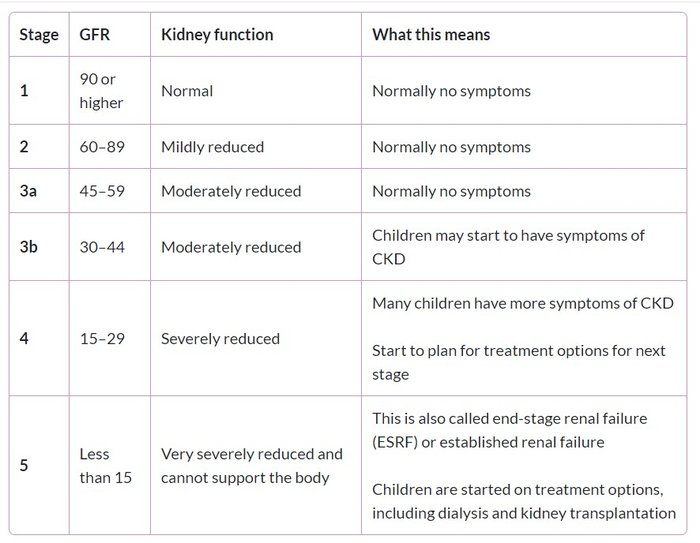

Stages of chronic kidney disease

There are five stages of CKD. Stage 3 is often split into two – stages 3a and 3b. The stages are defined by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The GFR measures the volume in millilitres (mL) that the kidneys filter each minute (min). This is adjusted for your child against a standard adult body size, which has a surface area of 1.73 square metres (m2). The GFR tells us how much blood the kidneys filter per minute – and how well the kidneys are working. This gives us an idea of the kidney function.

- The GFR for kidneys that are working at 100% (healthy kidneys) is 90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

- The GFR for kidneys that are working at 50% (half as well as healthy kidneys) is 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The table below shows the stages of CKD and the GFR.

Many children with CKD do not progress through all stages. Other children do reach stage 5, but how quickly this happens is different for each child. Some do not reach stage 5 CKD until adulthood, when they will be treated by a nephrology unit that treats adults with kidney conditions.

More about GFR and stages of CKD – in CKD introduction

Causes

CKD is very rare in children. It is caused by a number of conditions that affect the kidneys. Some of these are present at birth, and others start later in childhood. Not all kidney conditions cause CKD, and not all children with CKD progress to later stages.

Although the conditions are different, if they lead to CKD, the kidney function may get worse over time. In later stages of CKD, the kidneys are less able to filter blood and make urine. This means they are less able to remove waste products and control the amount of water and important chemicals in the blood. They are also less able to keep the blood’s pH balance (or acid-base balance) constant, which is important for health.

The kidneys have other jobs. These include controlling blood pressure, keeping bones healthy and strong, and stimulating the bone marrow to make red blood cells to carry oxygen round the body. Good kidney function also helps make sure children grow and develop normally. These jobs may be affected in later stages of CKD.

About your child’s care

Your child may see:

- your general practitioner (GP) – a family doctor in your local area

- a paediatrician – a doctor who looks after babies, children and young people with different health conditions. Your paediatrician may be in your local hospital or another setting in your area, such as a community clinic.

However, your child will start going more regularly to the paediatric renal unit, a specialised unit for babies, children and young people with kidney conditions, which may be in a different hospital to your own.

A team of healthcare professionals who specialise in helping children with kidney conditions will manage your child’s treatment plan, and support your child and family. The team may include a:

- consultant paediatric nephrologist, a doctor who treats babies, children and young people with kidney conditions, who will manage your child’s care

- renal nurse – a nurse who cares for babies, children and young people with kidney conditions

- paediatric dietitian – a professional who advises what your child should eat and drink during different stages of CKD, and helps you plan meals so your child gets the right nutrition

- renal social worker – a professional who supports you and your family, especially with any concerns about money, travel and housing related to looking after your child

- renal psychologist or counsellor – professionals who support your child and family, especially with emotional stresses and strains from having or looking after a child with kidney disease

- play specialist – a professional who uses dolls and other toys to help your child prepare for procedures such as blood tests and dialysis.

Questions to ask the doctor or nurse

- What treatment will my child need, and when?

- How will the treatment help my child?

- How can I help my child prepare for tests and treatments?

- How will you know whether or when my child will need dialysis and / or a transplant?

Tests and appointments

Your child will need to return to the hospital for follow-up appointments and blood tests. These will measure his or her kidney function and check for any complications.

It is important to go to all appointments even if your child feels well. If you cannot go to an appointment, please speak with your child’s healthcare team to arrange another date. More about tests and appointments

Medicines

Your child will need to start taking medicines and perhaps nutritional supplements

Your doctor or nurse will regularly review the medicines that your child is taking. The doses (amounts) or types of medicines may need to be changed, depending on your child’s needs and how he or she is responding to treatment.

Tips

- Speak with your doctor, nurse or pharmacist before giving your child medicines, including herbal medicines, or trying any types of complementary therapies. This is to make sure that these do not interact with your child’s treatment.

- Dot not give a type of medicine called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or diclofenac, without speaking with your paediatric nephrologist.

- If you are unsure about a medicine, ask your doctor or nurse what it is for and whether there are any side-effects.

- Keep an up-to-date list of all the medicines that your child is taking including the doses. Your child should carry this with him or her in case of an emergency.

It is important that you follow your doctor’s instructions on how much to give and when.

More general information about medicines on the Medicines for Children website

Fluids and blood pressure

Some children start to urinate (wee) less often, or pass less urine, or occasionally no urine. After some time, this leads to a build-up of water and salts in the body – fluid overload.

- This may cause swelling or puffiness in your child’s body – oedema.

- It may also cause your child’s blood pressure to rise – this is called hypertension.

Treatment

- Medicines: sometimes, medicines can help remove more water in the urine and/or control blood pressure.

- Fluids: often, children need to drink less fluid (such as water and juice) and eat less food with a high amount of water (such as soups and porridge). Your child may feel very thirsty at first – eating less salty food can help reduce thirst and helps control blood pressure. Your doctor will let you know how much fluid your child can drink. A paediatric dietitian can help you plan meals.

More about fluid overload and hypertension, including treatments

Passing too much urine

In other children with CKD, the kidneys cannot make concentrated urine. Instead, there is too much water in the urine. These children pass lots of weak urine, which looks lighter in colour. These children often need to drink lots of fluids to make up for the water they are losing in urine.

If your child passes a lot of weak urine and has diarrhoea or vomiting (being sick), speak to your doctor because he or she may be at risk of dehydration (not enough water in his or her body).

Nutrition and growth

All babies, children and young people need to eat a healthy, balanced diet to grow and develop. Children in later stages of CKD may develop a poor appetite, and not be able to eat as much. They may feel sick (nausea) or be sick (vomit), be more tired than usual and have low levels of energy.

A few children with CKD develop a high level of cholesterol (a fat) in their blood.

Treatment

- Diet: your child will probably need to follow a special diet to help make sure he or she gets the nutrition he or she needs.

- Nutritional supplements: your child may need to take nutritional supplements – drinks, powders, tablets or liquid medicine – to get the nutrients he or she cannot get from food.

- Feeding device: if your child cannot eat enough, he or she may need a feeding device. This uses a tube, placed in the nose, or sometimes through the skin, into the stomach, to give nutrients (and sometimes medicines).

Feeding your baby or child with CKD

More about nutrition and growth

Anaemia

The kidneys control the production of red blood cells, one type of living cell in the blood. Red blood cells have a substance called haemoglobin, which carries oxygen around the body. In later stages of CKD, there may be a drop in the amount of red blood cells and haemoglobin – this leads to anaemia. Children with anaemia often feel weak and tired, and may look paler than usual.

Treatment

Your child may need some medicines. These may include folic acid, and/or erythropoietin (EPO), which is injected with a needle. They may also need iron, which can be taken by mouth or given by injection.

Bone and heart problems

In CKD, the kidneys are less able to remove phosphate and potassium, chemicals that are found in many foods. This can lead to high levels in the blood, called hyperphosphataemia (too much phosphate) and hyperkalaemia (too much potassium). CKD can also lead to low levels of calcium, another important chemical in the body – this is called hypocalcaemia.

Renal bone disease

The kidneys are less able to control the levels of calcium and phosphate and to activate vitamin D – these are all needed to keep bones healthy. Children may develop renal bone disease (renal osteodystrophy) – the bones become less strong, and may not grow normally. Some children have no symptoms, but some have pain in their bones or joints, and are at risk of bone fracture.

This is a very rare complication, and does not normally happen if your child follows medical and dietary advice.

Heart problems

Hyperkalaemia can cause the heart to suddenly stop working properly. Your child’s healthcare team will check your child regularly and tell you how to stop this from happening.

There is a risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), a group of diseases of the heart and circulation (blood going round the body) – especially in adulthood. In children with CKD, this may be associated with:

- high blood pressure (hypertension) – this can affect the heart, as well as speeding up the loss of kidney function

- an imbalance (wrong amounts) of calcium and phosphate – after many years, this causes the blood vessels to get stiff and develop problems with blood circulation.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in adults with late stages of CKD.

More about bone and heart problemsTo reduce these serious risks – both in childhood and later in life – your child needs to carefully follow the treatment plan set by your doctor and dietician. This will probably include restricting which foods he or she can eat and taking medicines. It is crucial to do this – especially because there may be no symptoms.

Kidney failure

Stage 5 CKD is also called established renal failure (ERF) or end-stage renal failure (ESRF), when the kidneys cannot support the body. Your child’s healthcare team will help you prepare for the treatment needed at this stage, throughout the disease.

- Dialysis: some children need dialysis, which uses special equipment to remove waste products and extra water from their body. This may be needed if your child needs to wait a long time for a kidney transplant, or if your child goes into stage 4 or 5 CKD quickly.

- Kidney transplant: this is currently the best treatment for ERF in children, in which a healthy kidney from a donor is transplanted into their body. Sometimes this can take place before a child needs dialysis.

More about treatment for kidney failure

Supporting your child

This can be a difficult and stressful experience for your child and the whole family, including other siblings. You and your child will learn more over time about how to help manage and live with CKD.

Your child’s healthcare team is there to help you. They can provide support with your child’s education, accessing financial benefits and planning holidays around tests and treatments.

Speaking with other families of children with CKD can also be a huge support.

If you have any concerns or need additional support, speak with your doctor or nurse.

More about supporting your child with CKD – in CKD introduction

Older children and young people

Older children and teenagers may need to start taking more responsibility to manage their health. Your son or daughter may want to learn more about CKD, take his or her own medicines, and speak with the doctor or nurse on his or her own.

You will find the balance that works best for you and your child. If you need more support, talk with the healthcare team.

About the future

CKD is a lifelong disease. Unfortunately, there is no cure. Your child’s healthcare team will do what they can to help ensure the best and most suitable treatment, so he or she can live as healthy and fulfilling a life as possible.

Transition to adult services

When your child reaches teenage years, he or she will prepare to transfer from paediatric services (for children) to adult services. The timing is different for each person – though many will start being looked after by an adult nephrology unit by the time they are over 18 years old.

Many units have a transition programme, which starts some years before the transfer, to help adolescents to prepare.

Impact on adult life

Your child will need to take care of his or her health throughout life. As an adult, he or she will be supported by a new team. He or she should be encouraged to live a full and fulfilling life and go on to further education, working and having a family, etc.